No garden games in Tudor Oxford

Niall C.E.J. O’Brien

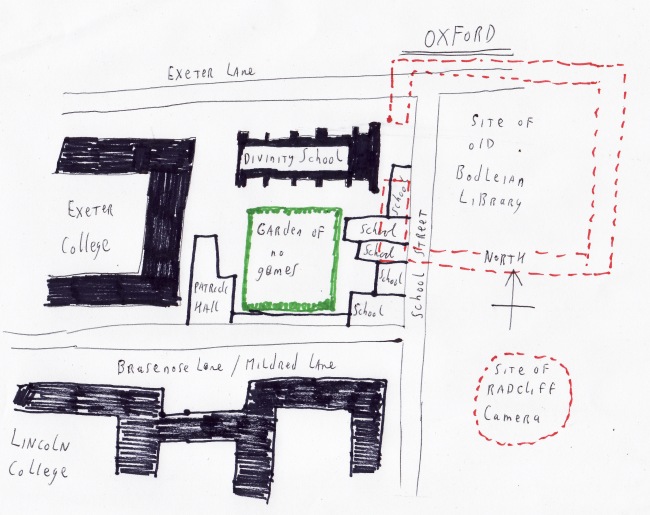

In March 1541 Balliol College made a lease of 20 years to John Hore, glover, and Agnes, his wife of a garden south of the Divinity School in Oxford. The annual rent for the garden was 6 shillings 8 pence.[1] The Divinity School is the oldest surviving purpose built building in university use and was constructed between 1427 and 1483.[2]

John Hore was possibly the son of Thomas Hore, husbandman, of Whitechurch, Shropshire. In March 1520 John Hore took out a 7 year apprenticeship with Elizabeth Jonson, widow, to train as a glover. By 1539 John Hore was married and was taking on apprentices in the trade of glove-maker.[3]

The garden that John Hore took on lease from Balliol came with restrictions. John Hore could not build any hog stile or dung hill in the garden as such would be a nuisance and be infectious to the schools surrounding the garden. This provision is understandable and without objection. Another restriction was that John Hore could not plant any tree in the garden which would stop the light entering the schools or cause window breakage. These schools, about four in number, belonged to Balliol and Exeter Colleges and bounded the garden on the east side. This restriction again seems reasonable and in a built up area sun light was important. In an age before electric light sun light was important for students to see what they were reading and writing, especially in the winter months.

The third restriction imposed on John Hore, which comes first in the lease agreement, has to do with holding garden games or more correctly, the ban on such. Balliol directed that no “bowling alley, butts, tennis court, or any other manner of pastime shall” be built in the garden. In the opinion of Balliol College, such past times would be a “hindrance and nuisance to students”.[4] Clearly there was to be no Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Club in Tudor Oxford.

Tennis began in France in the twelfth century when a small ball was struck by hand. It wasn’t until the sixteenth century that racquets came to be used. King Louis X was unhappy at playing tennis outdoors and had a court built within the palace. Other royal palaces across Europe soon adopted the indoor court. It was only with the invention of the lawnmower in 1830 that outdoor lawn tennis took off.[5] It is presumed that the ban of 1541 related to the building of an indoor tennis court in the garden as the word “to build” is use in the lease rather than to lay out a tennis court on the grass.

A garden photo in the absence of an actual photo of the garden in modern Oxford

The ban on garden games reflects the popular held idea of student life in third level education. Student life at college or university has a reputation for letting one’s hair down and doing anything and everything except actual study. This notion is no modern invention. Clearly the managers of Balliol College over five hundred and fifty years ago were very much aware of such a reputation with student life and sought in its property business to restrict such opportunities for doing anything and everything except study. For John Hore the garden was possibly for growing vegetables or herbs or storing materials he may need in his trade as a glover.

Yet it would seem fresh vegetables or garden games were not the only distractions from study for Balliol College. By 1550 three of the College’s schools, bounding the garden of John Hore had become run down and surplice to requirements. In 1550 the master and fellows of Balliol made a lease of 21 years to John Spenser, hosier of Oxford, of three schools in School Street to be made into a garden.[6] This newly made garden now forms part of the green in Radcliff Square. John Spenser was described as a woollen-draper in 1547 and as a merchant tailor in 1549 when he took on apprentices.[7]

In 1570 Richard Hanson, mercer of Oxford, took lease on the new garden from Balliol College, lately held by John Spenser.[8] One of the attachments on the lease to John Spenser was that he was to give up the new garden to the University during the term of the lease if the University desired to build on or near the site. The provision was also attached to the garden lease made to John Hore.[9]

By 1561 the 20 year lease which John Hore had on the garden of Balliol College had come to an end. In March 1566 the College made a new lease of the garden for 41 years to John Neale, Rector of Exeter College. Exeter College bounded the garden on the west. The value of the garden had increased since 1541 and John Neale was charged with an annual rent of 20 shillings.[10]

The same restrictions imposed on John Hore were again imposed on John Neale. There was to be no bowling alley or tennis court established in the garden nor any hog stile or dunghill. The option for the University to take over the garden if it wished to build on or nearby was also attached to the Neale lease.[11]

John Neale was deprived of the rector-ship in October 1570 after refusing to appear before the Visitors of Queen Elizabeth.[12] It was possibly in connection with this event that the tenancy of the garden was changed. Thus, in 1570 the garden, still without garden games, was held by John Lewis, baker of Oxford.[13] John Lewis first appears in the Oxford Apprentice Book in 1542 when he took on Richard Fallows of Shropshire. After 1542 John Lewis took on a good number of apprentices over the years. In 1574, his last year in the Oxford Apprentice Book, John Lewis took on three apprentices to train in the bakery trade.[14] By 1572 John Lewis was scaling back on his activities and the garden without garden games was held by Garbrand Harks.[15]

Garbrand Harks first appears as a mercer in 1554 when he took on Robert Gerret of Oxford as an apprentice. By 1562 Garbrand Harks had moved on to become a bookbinder. Garbrand Harks not only bound books but was also described as a book-seller. The job of a bookbinder and book seller was a nice number in a university town like Oxford where books, and the repair of books, were always in demand. In 1568 Garbrand Harks was still described as a bookbinder.[16] In 1589, Garbrand Harks held a tenement from Oriel College on the south side of High Street.[17] This tenement continued in the Harkes family until the late seventeenth century and is today a corner shop (number 108) where High Street meets King Edward Street.[18]

In October of 1572 Balliol College granted the garden along with the garden held by Richard Hanson and an adjoining garden held by Walter Baylie, doctor of physics, to Exeter College in exchange for a messuage and garden near Balliol College.[19]

The garden, which John Hore took on lease from Balliol in 1541, with the ban on garden games, still exists today between the Divinity School and Brasenose Lane. It is covered with trees and bushes with garden seats scattered about for students and visitors to take time out. By this foliage and layout the garden is still no place for lawn tennis or bowling.

Site map of the garden

====================

[1] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College (Oxford Historical Society, Vol. 64, 1913), p. 155

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divinity_School,_Oxford accessed on 26 June 2014

[3] Alan Crossley (ed.), Oxford City Apprentices 1513-1602 (Oxford Historical Society, New Series, Vol. 44, 2012), nos. 9, 102

[4] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College, p. 155

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tennis accessed on 26 June 2014

[6] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College, p. 156

[7] Alan Crossley (ed.), Oxford City Apprentices 1513-1602, nos. 214, 251

[8] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College, p. 157

[9] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College, pp. 155, 156

[10] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College, p. 156

[11] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College, pp. 156-7

[12] Rev. Charles W. Boase (ed.), Register of Exeter College, Oxford (Oxford Historical Society, 1894), p. 68

[13] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College, p. 157

[14] Alan Crossley (ed.), Oxford City Apprentices 1513-1602, nos. 131, 846-7, 867

[15] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College, p. 157

[16] Alan Crossley (ed.), Oxford City Apprentices 1513-1602, nos. 371, 545, 679

[17] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College, p. 207

[18] http://www.oxfordhistory.org.uk/high/tour/south/108.html accessed on 26 June 2014

[19] Rev. H.E. Salter (ed.), The Oxford deeds of Balliol College, p. 157

===============

End of post

==============